North-South antagonisms needled by tree ordinance

Richard Alles'

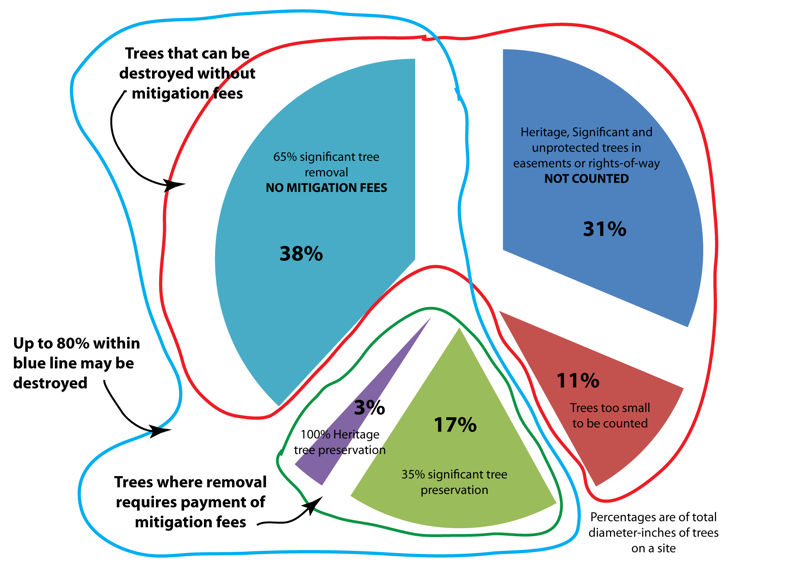

chart outlining how few trees are protected by proposed

ordinance.

Greg Harman

gharman@sacurrent.com

In the last 50 years, half of the world’s forests have been razed to manufacture “premium” beef and executive-grade ass wipes. (And, yes, we are including your boss in one of those categories.) Industrial agriculture has played a huge role, as have the expansion of cities.

Without a doubt the world needs more trees. Trees absorb unhealthy pollutants (including climate-destabilizing CO2), help keep smog levels in check, provide shade to offset the heat island effect, and much more.

But they don’t heal all wounds.

Concern that a proposed tree ordinance headed to a Council vote next week will disproportionately punish San Antonio’s South Side by setting a city-wide goal of 40-percent tree cover is expected to inspire some debate this week, according to at least one South Side Council aide. After all, ecologically speaking, trees are more of a North Side thing, with Hill Country forests nudging in as they do. The South, meanwhile, is dominated by the brushier South Texas plains ecosystem. So, to comply, developers there will have to plant more trees, some are complaining.

It's a point even the greens recognize.

“It’s definitely going to be a disincentive, it seems to me, if you’re having to plant in areas where historically its more a plains-type environment,” said Annalisa Peace, director of the Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance.

Don’t get her wrong. Peace praises the proposed ordinance for its attempt to close a much-abused ag-exemption loophole that has allowed too many land parcels to be clear-cut for development. She just worries it doesn’t do enough to steer development away from the North Sides’ Camp Bullis, golden-cheeked warblers, and the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone. She’d like to see the tree canopy raised to 55 percent over the recharge zone to help protect the city's primary source of drinking water.

“Our group wants to develop on the south, downstream of the sensitive areas,” Peace said. “This ordinance is slanted toward people that already have investments in those environmentally sensitive areas [to the north].”

Richard Alles of the Citizens Tree Coalition has pushed for years to get to this point. And yet he calls it a “mythology” to say that under this proposed ordinance “when a developer chops down a tree, he pays a fee. In fact, it’s just the opposite.” [See his chart at top.]

For starters, most trees are too small to be counted. Others are the wrong species. Even more are discounted for being rooted in the right-of-way or along easements — which can make up a third or more of a lot.

“It’s so hard to get across how week the ordinance is,” Alles said. “People look in the ordinance and they see a number that says you have to preserve 35 percent of the significant trees. They don’t read the part that says easements and rights-of-way are excluded. They don’t realize, that’s a third of the land. And this percent, this 35 percent, that only applies to the remaining two-thirds of the land.

“They can destroy 80 percent of what’s on a site without paying a penny in fees.”

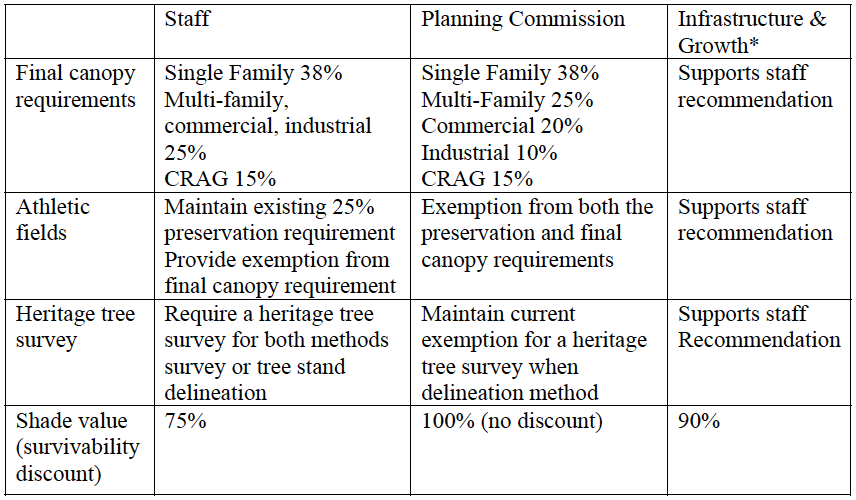

Keep that in mind as you read "final" canopy requirements:

So, step one is to bulk up the ordinance. When tree (that is: air, water, shade, habitat) protection becomes real, then we can get all North-versus-South with it.

There could be something to South-Side objections if the ordinance were a strong one. But tree people like Alles say as long as virtually any tree can still be axed under it, the proposed ordinance is less of a tree-preservation ordinance than a tree-planting directive. And it costs developers a lot less to plant a tree that build around one. That alone keeps the South attractive.

And yet it’s good to see some City leaders reportedly thinking in ecological terms, even if only reflexively and in defense of developers. Rooting on to that sort of thinking, San Antonio could take the tree ordinance as an opportunity to push development out of the environmentally sensitive North by making tree preservation as tough as possible. Then we could protect our aquifer recharge zones and help direct future growth in a direction with fewer environmental landmines.

Then, as the population shifts, some of the disparities among school systems might even start to be addressed. Things could get radical.

Subscribe

Queblog

South Texas political blogs

Jon's Jail

Journal

B

and B

Dig Deeper

Texas

Capitol

Annex

The

Walker Report

Grits for Breakfast

San Antonio

Politics (Express-News)

The Kendallian

Off the Kuff

South Texas Chisme

Concerned Citizens

TexasVox

The Narcosphere

Rhetoric &

Rhythm

Did we miss your favorite?

Email it to

us

Meta

Search by:

Cuisines (746)City (734)

Neighborhood (116)

Reviewed (199)

Critic's pick (56)

Open 24 hours (17)

Late dinner (310)

Brunch (58)

Takeout (156)

Delivery (42)

Outdoor dining (128)

Kid friendly (168)

Serving

Food (62)Microbrew (2)

No alcohol (24)

Featuring

Dance floor (24)Darts (8)

Billiards (16)

Games (8)

TV (27)

Outdoor seating (35)

Dress code (2)

No smoking (17)

Wheelchair access (57)